Revisiting grief: The Gul (& Roses), and secrets

Keep your secrets, under the rose. Carpets under your feet.

I revisited The Gul, written shortly after he died in 2022.

When my father died in 2005, The Gul threw me a life preserver for a year, then I "checked in" with him and later “checked on” him almost weekly, for free, for another 15 years. My father had hung my moon and my sun, too. The shards of glass reassembled.

He was a "force of nature," a typhoon, too much for some and not enough for me. Of late, I think about the alternative timelines had he lived another five years.

It was not a tragedy, as he survived bladder cancer for 18 years, which hit him eight years earlier than I am now, but his cardiologist's three-pack of Marlboros a day habit sealed his fate; lungs don't regenerate, and my fate, too, as we have Methuselah genes and I soon have cardiac surgery, so I think about the miracles of cardiology I grew up listening to at the dinner table.

When April 13th approaches, I think of him, especially now, when so many people I know are grieving the true tragedies of soldiers they knew, hostages and other loved ones, and too many children placed in front of them as shields by a death cult. This fact does not absolve anyone.

It's been accessible only to paid subscribers, but he shared many worthwhile things that seeped in:

“We can't control who we lose. And we can't spare ourselves the pain of it, nor should we."

When you meet someone who has experienced a loss, you recognize the scar. Scars heal, and yet they don't. It's a punishment we all understand: Jews, Muslims, and Gentiles. I am grateful for my loss because it allows me to recognize others' suffering, even the hidden ones.

Here it is at the end of Shabbat for some:

No, not guns. Guls.

It is Ottoman Turkish (gul) derived from the Persian word gol (گل) which means flower or rose. It can be a family name, too. I knew a man I called The Gul. He was a collector of carpets and secrets, and preferred to own Oriental rugs over shares.

“They just don’t make them any more.” he said, about rugs. I learned a lot from The Gul. About keeping a secret, and about people who cannot. And, they just do not make certain types of men anymore. Maybe, a few.

Guls are medallions, often octagonal, and often angular on an octagonal plan, though they can be rounded within the constraints of carpet-weaving, and some are lozenge-shaped (rhombuses). They usually have either twofold rotational symmetry or mirror reflection symmetry (often both left/right and up/down).

Gul were historically described in the West as being elephant's foot motifs. Other Western guesses held that the gul was a drawing of a round Turkmen tent, with lines between tents representing irrigation canals; or that the emblem was a totemic bird. To me, a rose.

Here is what I mean, a Konya 18th carpet with Memling gul design. There is a row of triangular amulet motifs (Muska) at top and bottom; each of the four lower gul has a star motif (Yıldız) at its center.

The early Nederlandish painter Hans Memling 1479 Triptiek (Tryptich), the central panel depicts The mystic marriage of Saint Catherine of Alexandria (the patron saint of nuns). It is in the Memling Museum in Brugge. It is part of the St. John Altarpiece Tryptich of the two Johns, Baptist and Evangelist, with the central focus depicting the Virgin and Child with saints and the Christ child holding an apple in one hand and slipping the ring on St. Catherine’s finger, to signify the mystic marriage, with the other hand.

At their feet, a Turkmenistan carpet with guls. So, roses, in the carpet under the Virgin’s feet. Memling did this so often, they became known as Memling carpets and they draw attention to an important person. Rugs from the Islamic world had seeped, then flooded, into Western Europe by the 15th century, a leading trade encounter between the two worlds. In art, there were Holbein carpets, Bellini carpets, Crivellis, Lotto carpets and Memlings.

Cupid gave a rose to Harpocrates (the Hellenistic god of silence) so that he would not reveal the secrets of Venus.

It was the Islamic world that gave us carpets, and guls, too.

The panel above though is thought to be a sacra conversazoione, a sacred conversation, an Italian Renaissance genre depicting the Virgin and Child amidst a group of saints, with angels in frequent attendance.

You will see why I called him The Gul.

Guls keep secrets, the sacred conversations they witness. No notes. A good gul is hard to find, in this day of diagnosis for reimbursement and the demand of state laws requiring note taking.

The Gul had been a music major at Princeton, preferred playing jazz piano, then composed a Broadway musical and realizing it was not a living, went to medical school, then the Psychoanalytic Institute (Columbia, “Chock Full O’Nuts,” he called it), taught a few other analysts how to save lives, then he found me, through a mentor whose carpet collecting Swiss-Deutsche Jewish refugee, whose house had run out of surface area from his rug collection. The mentor, to get me to talk, had taught me chess, about Roman coins, and “Oriental” rugs. What we know now is Islamic art.

Gul had one office rug, under his feet, he never took notes, and he did not charge me for the last 25 years of friendship. It was not a therapeutic relationship because then he would have to take notes, which I could not allow, and pay him, which he would not allow. His solution. Sit, never silent, and remember everything he heard.

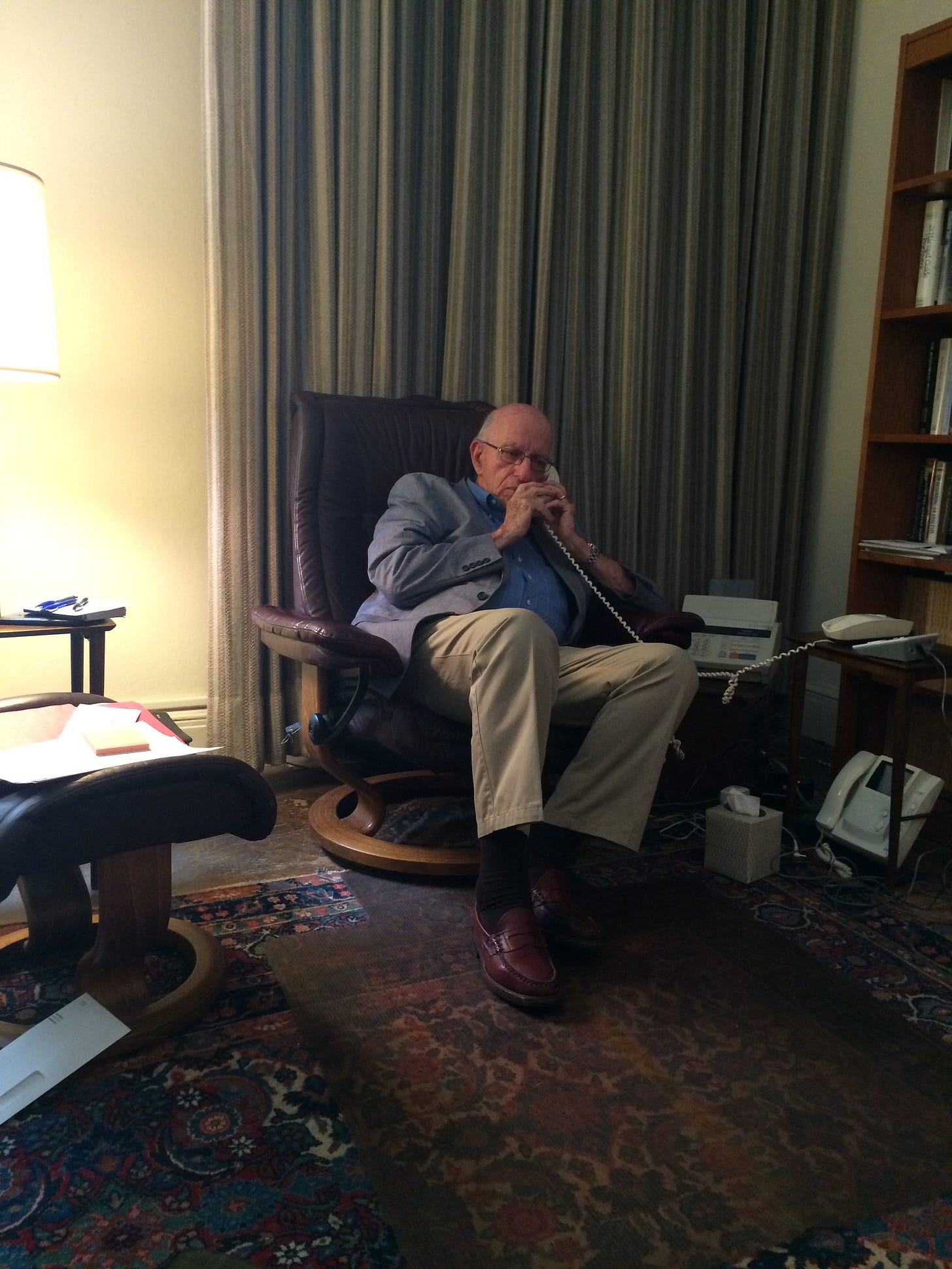

Here is The Gul multi-tasking:

Note the essential therapy equipment: loafers, the fax machine (to send scrips; he was allergic to laptops), and the rug—rug-pre-hearing aid phone with answering machine. You can almost see his friend Dr. Otto Kernberg’s “Object Relations and Clinical Psychoanalysis,” the definitive tome on Borderlines ((DSM-5 301.83 (F60.3)) because they don’t have object constancy, on the shelf behind him, but never truly on the shelf, which he gifted me. He and Otto taught me about splitting, the frantic fear of abandonment, and how to help those who are attached to us.

One day, Gul said to me:

”You know, you’re not the only one who remembers everything you hear, every face you see,” lightly tapping on his hearing aid, whose battery often drained as he dozed off in his chair. A music man’s memory, for notes. A spy’s memory for faces.

“But what about the State or a subpoena?” I asked.

“What are they going to do to me, take away my license, put me in Rikers, I’m 90?”

I never took notes in College, graduate school, or the later academies, except for drawings in art History, Calculus, and Microeconomics. My names are not so good anymore. Still, neurodivergent.

But, The Gul.

Trusting Gul’s wisdom and discretion guided me through the shoals of losing, then regaining, several pillars of my life. Still, there is another. He knew I detached poorly, but knowing the theory was less than therapeutic he said, over and over, two things:

“There are two medicines for all ills-Time and Silence.” Then, he would say,“Wait and Hope.”

Never, '‘move on.”

I will not bore you with my Book of The Gul sayings, and I later learned that these two mantras were both quotes from Alexandre Dumas’ Le Comte de Monte-Cristo, a novel about a man who is wrongfully imprisoned, escapes from jail, acquires a fortune, and sets about exacting revenge on those responsible for his imprisonment. Not any resemblance to me. Un homme trop différent de moi.

Not exactly what one expects from a Columbia-trained and training psychoanalyst, but I was on the pro bono plan, with Methuselah genes, so we both knew I could do it—wait in silence. He did not want me to emulate Monte Christo again and knew that Dumas’ story would be difficult to resist. I have not always been orthodox about doing nothing, but my silence regarding what friends tell me or even show me is forever a sacred conversation.

By definition, the Gul was unprofessional with me, and I often give silent thanks for that wisdom. Because of the Gul, I also know that while grieving cannot be put off forever, do not rush into it. In a few days, he will be gone, almost a year, and silence and grieving a friend’s loss cannot be put off forever.

Here we are.

As an example of his unprofessionalism, he often spoke of his adult children, with great admiration and affection, with an impish grin, in between the phone calls that he fielded in our sessions. It was his lesson in patience and the power of silence: "Just sit, I will be back," he said.

I never left his office without a grin on my face, which was a challenge, having had several medical issues that had damaged my facial nerve. It may seem trite, but he saved my life more than once, bolstered my resilience, and tempered my furnace. Tempered, not extinguished.

I will remember The Gul. I know secrets and keep them. Just not this one, under the Rose, with a Bukhara carpet now under my feet.

Still, there is another. Love and hate—it’s such a thin line. I await in silence: Paris in the rain, Colorado’s blue skies, and a golden puppy with wet fur.

Waiting and hoping, time and silence. I remember The Gul (1929-2022).

“All human relationships must end, and the threat of loss, abandonment. And, in the last resort, of death, is greatest where love has most depth; awareness of this also deepens love.”

—Otto Kernberg, M.D. in “Object Relations Theory and Clinical Psychoanalysis.”

©Philippe du Col, 2025 🍊